The previous owners left behind a black-out roller blind and an empty curtain track so I thought I would have a go at curtains.

I was inspired, in part by one of my Christmas presents [am I really blogging about Christmas presents in April?] Sewing Machine Basics by Jane Bolsover...

… which contains instructions on how to make sheer curtains…

...and partly by a pair of poly chiffon curtains that came from one of The Much Belovéd's previous residences. The curtains would not typically be my first choice of fabric but they were unlikely to be used again elsewhere, sheer and would therefore work well with the existing blind, free and available and therefore of no consequence should I happen to ruin them.

I laid a curtain out on the floor which was the only place big enough to do so. The top of the curtain was finished with a tab top and the bottom partially finished with an overlocker. I suppose the idea was to hem them yourself to the required length. I rather suspect that this pair of curtains may have been supplied with their own packed of fusible webbing for just that purpose.

This operation left me with a long piece of cloth, hemmed on two sides, overlocked across the bottom width, with raw across the top. Each curtain was more or less the width of my window and, from what I had read, using both would give me a nice fullness when gathered over the window.

The next step was to turn my attention to that overlocked bottom edge. I decided to look upon that partial finishing as a gift on this slippery sliding shifting fabric and use it to help me produce my hem.

I began by turning up 1½ inches. I turn the folded edge up again so that the line of overlocking was enclosed by my first fold. This gave the bottom hem a triple thickness and a nice bit of heft which should help with the hang of the finished curtains. I felt the need to use a great many pins to hold this turning in place. The fabric handled something like a cross between a crisp packet and a bin liner.

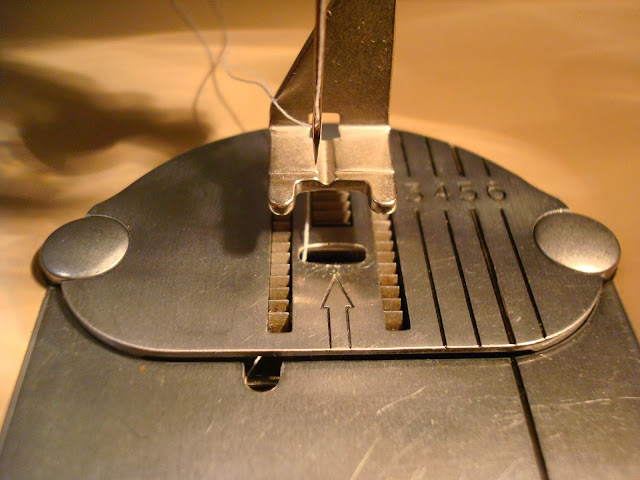

The instructions in the book are to pin and then hand baste (tack) every bit of sewing you do. I am sure that this approach produces fantastically neat results… … eventually. A big apology to the purists but I just couldn't face that kind of investment of time in a piece of second hand polyester. I managed to produce a decent hem using plenty of pins and the 1936 Singer 99K hand crank. The machine handled a fabric which would not be invented until five years after it was built pretty well I thought. I was sure to use a light tension to avoid puckering though. I used a cool iron to press the hem because I was terrified the fabric might melt. It just about holds a crease but not for very long. More on how things went at the other end of the curtain next time!